The Healing Potential of Iboga

There has been extensive study of the iboga plant and its substantial potential to treat deep physical, emotional, and psychological challenges. As conventional treatments often provide limited relief for those struggling with complex conditions such as substance abuse disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, there have been efforts to seek alternative pathways to wellness.

This post is the second part of our entheogens blog series, following the first post on ayahuasca and continuing the exploration of entheogens, their cultural origins, and their relevance to modern health care. Here, we are extending our understanding of the remarkable healing potential of an ingredient from the iboga plant, found in Central West Africa, that has been used for centuries in Indigenous spiritual and healing practices, and has recently been used in studies, offering a treatment for psychological, emotional and physical complex conditions. Notably, it has shown promise in addressing traumatic brain injury (TBI), a condition that has been exceptionally difficult to treat within the parameters of conventional medical approaches.

The foundational approach to examining how this ancient plant offers guidance and healing is to first respect its historical and ceremonial uses as the root of its healing potential. From there, building on modern clinical research and applying it in contemporary contexts can be honored through a decolonized lens, which emphasizes that therapeutic practices remain accountable to traditional knowledge and traditions. In this way, it ensures that the communities that have tended this medicine and the ecosystems on which it depends are protected and supported rather than exploited. It supports a relationship grounded in consent, respect, embodied gratitude, and reciprocal care for both the people and the plant.

To understand its modern applications, it is important to first explore how Iboga has been historically and ceremonially used.

Historical and Ceremonial Use

Iboga has been used for centuries in religious ceremonies and traditional medicine by the Gabon and Congo cultures (Lotsof, 1995; Spinella, 2001). The Fang peoples of West Africa say that the San people were the first to find the iboga shrub Tabernanthe iboga in the rainforest and that the San ancestor Bitamu is contained within iboga (Rätsch, 1998). During the early 20th century, the Fang people of Gabon in equatorial West Africa began using iboga, calling it Bwiti. The Fang Bwiti cult is a syncretic Neo-Christian religion in which the powdered iboga roots serve as the Eucharist (Ott, 1995).

The bwiti cult and other iboga-using societies take iboga to make contact with the ancestors and “break open the head” (Schultes & Hofmann, 1979, p. 112). The iboga roots are yellowish in color and are traditionally scraped into a powder or made into an infusion for drinking (Schultes & Hofmann, 1979). In Gabon, hunters use small doses to stay awake and reduce thirst, hunger, and fatigue (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies [MAPS], 2003; Spinella, 2001). Members of the Bwiti religion use it at much higher dosages as a sacramental hallucinogen in rites of passage (Alper & Lotsof, 2007).

Building on these traditional practices, researchers have extracted ibogaine from the plant to study its effects in modern therapeutic contexts.

From Plant to Medicine: Ibogaine and Its Effects

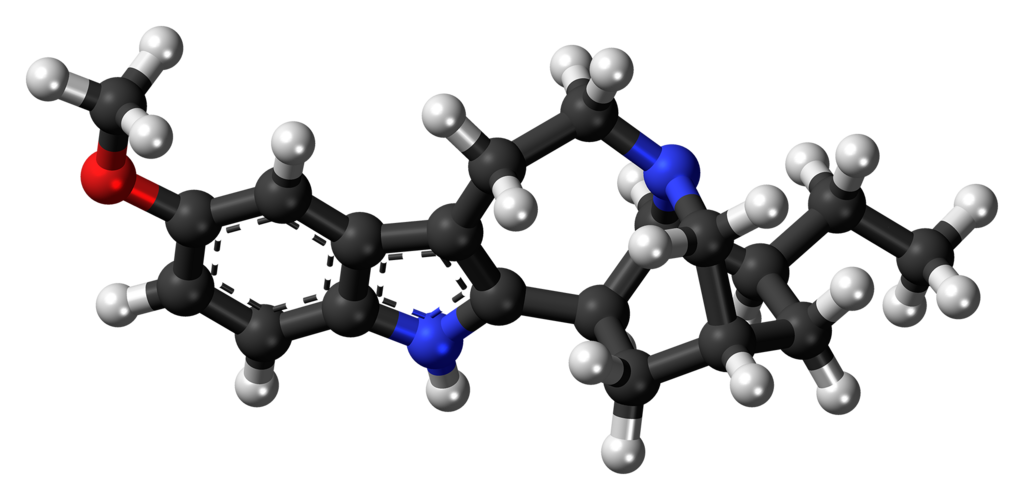

Ibogaine is an indole alkaloid that was first isolated from the roots of the Tabernanthe iboga plant in 1901 (Ott, 1995). It is also found in Tabernanthe crassa (MAPS, 2003; Popik, 1998). Ibogaine is a nonaddictive extract from the plant (Lotsof, 1995; Popik & Glick, 1996). Its active metabolite, noribogaine, is an atypical opiate that appears to alter the addiction circuit (Mash, 2010) by acting on both opioid and serotonergic receptors (Mash, 2010), which likely accounts for the elimination of opiate cravings and its hallucinogenic qualities, respectively.

The effects of ibogaine are physically, psychologically, and spiritually profound (Mash, 2010), and both animal tests and human experience result in an almost immediate elimination of symptoms of withdrawal and reduction in craving following the first ingestion. During anibogaine treatment, individuals with opioid or opiate addictions experience a lifting of the physical symptoms of dependence within 30 to 45 minutes following ingestion. For some, this is when a visionary phase (MAPS, 2003) begins.

Ibogaine is used in Europe and North America as a ritual hallucinogen for psychological insight or spiritual growth (Alper & Lotsof, 2007). Ibogaine was recently patented in the United States and is studied for its use in treating addiction (Halpern, 1996). There are numerous clinics in Caribbean countries, Mexico, and Europe where individuals may seek treatment.

A New Zealand study found that a single session can reduce withdrawal symptoms and support sustained opioid cessation or reduced use. In addition, they found depression scores significantly decrease showing that legal access may improve treatment outcomes when providers collaborate with healthcare providers.

Beyond addiction, emerging research shows ibogaine may also support recovery for complex neurological conditions, such as traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Ibogaine for treating Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

While ibogaine’s benefits for addiction and spiritual insight are well-documented, emerging research suggests its therapeutic potential may extend to populations with complex neurological conditions, including veterans living with TBI.

In a new observational study, researchers explored whether ibogaine, administered with magnesium for cardiac safety, could provide relief to veterans living with the lasting effects of traumatic brain injury. They evaluated 30 male Special Operations veterans before, immediately after, and one month following treatment.

The results were remarkable: veterans showed significant improvements in overall functioning, with even greater gains one month after dosing. Symptoms of PTSD dropped sharply, and measures of depression and anxiety declined in ways rarely seen in populations with chronic TBI-related conditions. Importantly, no serious or unexpected adverse events were reported, and magnesium appeared to mitigate cardiac risks. While these findings are preliminary, they suggest a potentially groundbreaking therapy for a population that traditional medical approaches have long underserved.

As with all potent substances, understanding safety, toxicity, and clinical observations is essential before exploring further applications.

Safety, Toxicity, and Clinical Observations

There have been some case reports of death during ibogaine use and there is concern about its potential to generate cardiac arrhythmia (Kovar et al., 2011).

With most ibogaine-related deaths, postmortem data links serious pre-existing medical conditions, mainly cardiovascular, and/or polysubstance use. These additional risks arise from withdrawal-related seizures and the unsupervised use of ethnopharmacological iboga preparations. Nonetheless, with increased use of these types of treatments, it is essential that the risks are addressed and disclosed, in addition to rigorous medical assessments and monitoring (Noller, Frampton, & Yazar-Klosinski, 2018).

Ibogaine’s potential to generate cardiac arrhythmia stems from its impact on cardiac ion channels, particularly its tendency to prolong the QT interval, which can precipitate dangerous irregular heart rhythms in “ patients with cardiac comorbidities and concurrent medication” (Köck, Steding, & Bschor, 2022). These safety concerns can be mitigated with rigorous medical assessments, continuous monitoring and strategies such as magnesium co-administration as a protective strategy (Köck, Steding, & Bschor, 2022).

Beyond physiological safety, the experiential effects of ibogaine require skilled practitioner support to ensure a safe and meaningful experience.

Overall, iboga produces mild entheogenic effects, but the loss of ego associated with other entheogens, like LSD and psilocybin, does not occur. Discomfort may occur, usually caused by the subject fighting against the experience. This can be mitigated by having the client open his or her eyes to make the visions recede and by the presence and reassurance of the practitioner (MAPS, 2003).

References

Alper, K. R., & Lotsof, H. S. (2007). The use of ibogaine in the treatment of addictions. In M. J. Winkelman & T. B. Roberts (Eds.), Psychedelic medicine: New evidence for hallucinogenic substances as medicine (Vols. 1–2) (pp. 43–66). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Halpern, J.H. (1996). The use of hallucinogens in the treatment of addiction. Addiction Research, 4 (2), 177–189. Abstract retrieved from http://www.maps.org/newsletters/v06n4/06407abs.html

Köck, P., Steding, J., & Bschor, T. (2022). A systematic literature review of clinical trials and therapeutic applications of ibogaine. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 138, 108717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108717

Korn, L. E. (2021). Rhythms of recovery: Trauma, nature, and the body. Routledge.

Lotsof, H. S., (1995). Ibogaine in the treatment of chemical dependence disorders: clinical perspectives (a preliminary review). MAPS, 5 (3), 16–27. Retrieved from http://www.ibogaine.desk.nl/clin-perspectives.html

Mash, D. C. (2010). Ibogaine therapy for substance abuse disorders. In D. Brizer & R. Castaneda (Eds.), Clinical addictions psychiatry (pp. 50–60). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Noller, G. E., Frampton, C. M., & Yazar-Klosinski, B. (2018). Ibogaine treatment outcomes for opioid dependence from a twelve-month follow-up observational study. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 44(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2017.1310218

Ott, J. (1995). The age of entheogens and the angel’s dictionary. Kennewick, WA: Natural Products

Popik, P., & Glick, S. D. (1996). Ibogaine: A putatively anti-addictive alkaloid. Drugs of the Future, 21(11), 1109–1115.

Spinella, M. (2001). The psychopharmacology of herbal medicine. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Schultes, R. E., & Hofmann, A. (1979). Plants of the gods: Origins of hallucinogenic use. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Leave a Comment