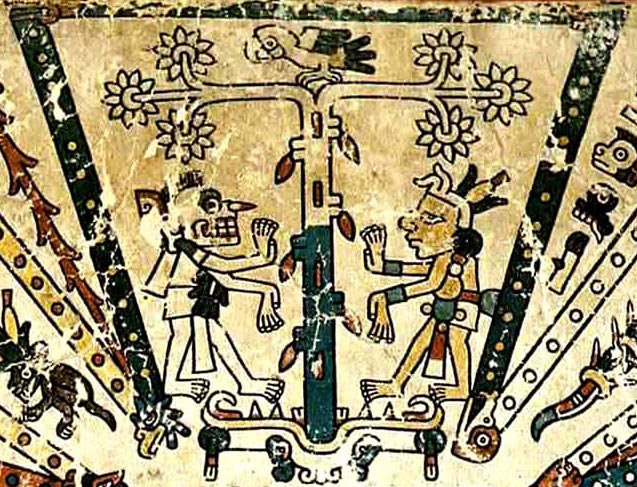

Cacao holds deep cultural, spiritual, and ecological significance for Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Once central to creation stories, rituals, and local economies, it was later transformed into a global commodity under colonization. Today, communities are revitalizing cacao’s sacred and ecological role, honoring ancestral knowledge.

Cacao, or Theobroma cacao, holds profound cultural, spiritual, and ecological significance, particularly among Indigenous communities in Mesoamerica and South America. For thousands of years, it has served as both nourishment and sacred symbol, reflected in creation stories, ceremonies, and local economies.

Cacao’s ties to the themes of life and fertility date back several millennia, with evidence found in oral history—like in the Maya creation story, the Popol Vuh—and archaeological evidence. However, the onset of colonization disrupted these beliefs and transformed cacao into a global commodity. The contemporary effects of this shift manifest in large-scale productions that threaten traditional farming methods and biodiversity, endangering both culture and ecological health. Yet across many regions, Indigenous communities are working to restore cacao’s spiritual and ecological role. Through practices rooted in ancestral knowledge and cultural sovereignty, these communities honor cacao’s sacred origins and forge more sustainable futures.

Botanical Origins of Cacao and Its Early Significance

Cacao or Theobroma cacao is an evergreen tree native to the rainforests of South America. It grows 4–8 meters tall and features large, glossy leaves, small pinkish flowers on its trunk and branches, and football-shaped pods that ripen into shades of yellow, orange, or red. These pods contain cacao beans embedded in sweet, white pulp (Williams, 2024). Today, cacao sustains approximately six million smallholder farmers, predominantly in West Africa and parts of Asia, where it is a vital economic crop (Díaz-Valderrama et al., 2020).

Cacao’s chemical composition includes caffeine and theobromine, rare alkaloids that act as stimulants and vasodilators, contributing to cacao’s popularity in Europe, where it became one of the first alkaloid-rich beverages available for consumption. Cacao is also a nutrient-dense food, providing minerals like magnesium and copper, as well as antioxidants and psychoactive compounds that enhance its value (Wootton, 2024).

The term “cacao” has contested origins, with some linguists tracing it to the proto-Mixe-Zoquean word kakawa, while others argue it is a Maya derivation inspired by the calls of monkeys eating cacao pods. This explanation reflects Indigenous perspectives that honor animals as integral to the ecosystem and center the natural world, contrasting with Eurocentric models, such as Linnaeus’s designation of cacao as the “food of the gods” (Wootton, 2024; Thompson & Law, 2020). This brings to light an epistemological contrast between Western and Indigenous cultures. Cacao began to be described in hierarchical, human-centric terms, stripping it of its ecological and cosmological significance. In contrast, Indigenous epistemologies embed cacao within a broader worldview, integrating it into both spiritual and agricultural frameworks.

Cacao originates in the Upper Amazon, a region rich in genetic diversity that spans modern-day Colombia and Ecuador. Eleven genetic groups, including Criollo and Nacional, highlight the plant’s evolutionary and cultural significance (Lanaud et al., 2024). Evidence suggests that cacao was first domesticated around 3350 BCE in the Upper Amazon, although its spread to Mesoamerica remains a topic of debate. Some researchers propose that trade routes introduced cacao to Mesoamerica from the Pacific coast of Ecuador, as supported by DNA analyses of Valdivia-era pottery containing cacao residue (Lanaud et al., 2024). Other theories suggest that overland routes brought Criollo cacao to Mesoamerica from Venezuela and Colombia. Regardless of the pathway, archaeological and genetic evidence confirms cacao’s origins in South America, even as it became deeply embedded in Mesoamerican culture.

“The Maya’s sacred text, the Popol Vuh, highlights cacao’s cosmogonic significance, linking it to the creation of humanity and the divine cycle of life and death.”

Cacao in Mesoamerican Agriculture and Society

The domestication of cacao in Mesoamerica dates to approximately 2000-1000 BCE, during the Early Formative period. Criollo cacao, known for its delicate flavor, was cultivated in the warm lowland regions of Mexico, where it became a highly valued agricultural product (Díaz-Valderrama et al., 2020). Studies suggest that the Olmecs were likely the first to domesticate cacao and develop chocolate production. Pottery from the Olmec capital of San Lorenzo reveals the presence of cacao-based beverages as early as 1800 BCE. The Olmecs also established cacao’s symbolic associations with blood, sacrifice, power, and fertility, linking it to rituals and elite status (Caso, 2020).

In Maya culture, cacao played a central role in spiritual and social practices. Classic-period vases decorated with glyphs and hieroglyphs describe cacao varieties and their ceremonial use, while chemical analyses confirm their presence in elite rituals. The Maya’s sacred text, the Popol Vuh, highlights cacao’s cosmogonic significance, linking it to the creation of humanity and the divine cycle of life and death (Sacco, 2022). These traditions persisted into the Mexica period, where cacao was used in offerings to gods such as Quetzalcoatl and consumed as chocolatl by the elite. Records indicate that Tenochtitlan received at least 22 tons of cacao beans annually as tribute from subject states, emphasizing its economic and ritual importance (Díaz-Valderrama et al., 2020). However, colonial accounts, such as those by Bernardino de Sahagún, often focused on cacao’s economic uses, neglecting to focus on its deeper spiritual and symbolic dimensions (Sacco, 2022).

Spiritual and Social Roles of Cacao in Indigenous Life

Prior to the Conquest, Cacao held great religious and social significance across many Indigenous cultures of the Americas. In South America, some Indigenous groups, such as the Machiguenga and Tukuna, used cacao pulp for food and beverages, while others consumed cacao beans. Archaeological findings from the Mayo-Chinchipe-Marañón Basin suggest early domestication, as evidenced by artifacts featuring Amazonian motifs, including monkeys associated with cacao trees (Díaz-Valderrama et al., 2020). In Mesoamerica, residues on Olmec ceramics confirm cacao’s integration into burial offerings and rituals tied to fertility, power, and the cosmos (Powis et al., 2011). Among the Maya, cacao was and remains a symbol of social harmony, used in contemporary rituals to resolve conflicts and celebrate unions (Wootton, 2024). However, colonial exploitation disrupted these traditions by commodifying the fruit. The desacralization of cacao under colonial systems represented not just an economic shift but also an erasure of deeply ingrained spiritual practices, which modern decolonial movements seek to recover in order to reaffirm cultural identity and autonomy.

Colonial Disruption and Indigenous Cacao Revitalization

Colonization fundamentally altered cacao production, with Indigenous labor exploited to expand plantations for European markets (Díaz-Valderrama et al., 2020). Epidemics decimated populations, while the imposition of Christianity desacralized cacao, reducing it to a commercial crop (Stanley, 2019). Among the Mopan Maya in Belize, colonial impacts persist today, as cacao’s spiritual role has been replaced by its commodification under Protestant influence since the 1970s. Colonial exploitation, along with the rise of Protestant missionary influence in Belize, disrupted Indigenous cacao traditions. Spiritual practices were considered pagan under Christian orthodoxy, assisting the crop’s shift from a culturally and spiritually significant plant to one of mere monetary value. The resulting monocultural plantations contributed to ecological instability, exemplified by the spread of the Monilia fungus, highlighting the detrimental effects of this desacralization and loss of Indigenous Knowledge Systems (Stanley, 2019).

Indigenous-led decolonial efforts, however, are reclaiming cacao’s cultural and ecological significance. In Ecuador, for example, a Kichwa community is utilizing traditional cultivation techniques to preserve original cacao varieties—improving disease resistance and restoring genetic diversity (Vernik, 2020). This represents a broader movement to reclaim Indigenous sovereignty in cacao production. The integration of Indigenous knowledge systems into global frameworks provides space to address ecological instability while honoring cultural heritage (Lavoie & Olivier, 2023).

Honoring Cacao through Indigenous Knowledge and Sovereignty

Cacao’s story is a tale of cultural survival in the face of uprooted Indigenous traditions and ecological practices. Today, Indigenous movements are reviving traditional methods to reclaim cacao’s cultural and ecological significance. These efforts restore ecological stability, preserve cultural heritage, and promote sustainability. As global attention shifts toward sustainable practices, integrating Indigenous knowledge is crucial for restoring balance and achieving reparative justice.

References

Caso, L. (2020, June 23). A culture of cacao and chocolate. ReVista. https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/a-culture-of-cacao-and-chocolate/

Díaz-Valderrama, J. R., Leiva-Espinoza, S. T., & Aime, M. C. (2020). The history of cacao and its diseases in the Americas. Phytopathology®, 110(10), 1604-1619.

Lanaud, C., Vignes, H., Utge, J., Valette, G., Rhoné, B., Garcia Caputi, M., … & Argout, X. (2024). A revisited history of cacao domestication in pre-Columbian times revealed by archaeogenomic approaches. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 2972.

Lavoie, A., Thomas, E., & Olivier, A. (2023). Local working collections as the foundation for an integrated conservation of Theobroma cacao L. in Latin America. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 1063266.

Powis, T. G., Cyphers, A., Gaikwad, N. W., Grivetti, L., & Cheong, K. (2011). Cacao use and the San Lorenzo Olmec. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(21), 8595-8600.

Sacco, M. (2022). Rediscovering the Ecology and Indigenous Knowledge of Cacao Forest Gardens and Chocolate (Doctoral dissertation, Trent University (Canada)).

Stanley, E. (2019). Religious Conversion and the Decline of Environmental Ritual Narratives. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature & Culture, 13(3)., Nature & Culture, 13(3).

Thompson, J., & Law, A. Hot for Chocolate: Aphrodisiacs, Imperialism, and Cacao in the Early Modern Atlantic 5 jul 2020· Dig: A History Podcast.

Vernik, M. (2020). Create space for Indigenous leadership to preserve agricultural biodiversity (LULI Working Paper No. 002). Global Development Policy Center, Boston University. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2020/06/LULI-GDP_WorkingPaper_002_EN.pdf

Williams, S. (2024). Ceremonial cacao as a therapeutic tool in psychotherapy. An exploration of therapists’ experience of and use of grounding techniques in their work with developmental trauma in adults in Ireland, 10.

Wootton, C. K. (2024). Communion with Cacao: Working With Cacao as a Sacred Medicine in a Modern Therapeutic Context (Master’s thesis, Pacifica Graduate Institute).

Leave a Comment